The Art World, "Beasts": Leon Golub's humanism

By Peter Schjeldahl

For The New Yorker

May 17th, 2010

An exciting show of late, rude oil stick drawings by Leon Golub, at the Drawing Center, advances the career of an artist whose death, in 2004, at the age of eighty-two, hardly slowed his momentum. That's because Golub- an eternal Chicagoan, though he lived in New York after 1964 (following a five-year stint in Paris)- hasn't properly arrived yet, but he will. The Art world will tire of resisting his Expressionistic work on grand themes of political violence, with its roots and tendrils in human nature. Or, rather, we will come to regard our resistance as he did: as something that you'd expect, and might enjoy provoking, in a culture that is insulated against worldly realities by persnickety aestheticism. I have foremost in mind Golub's great art of the nineteen-eighties. Those vast, ungainly, disturbingly infectious paintings, their pigment scraped down with meat cleavers into the tooth of the unstretched canvases, portray mercenaries and torturers at work and play in indeterminate locales, recalling Kandisnky's remark on the space of abstraction: "Not here, nor there, but somewhere." The thuggish men, robustly imagined, with hints from such sources as Soldier of Fortune, are as specific as people you know well, though probably wish you didn't. They confront us with friendly grins as often as with ominous scowls. Their victims are not particularized. (That's what victimization is: reduction to nonentity.) The work, from the Reagan era of Iran-Contra and dirty wars, strummed the nerve endings of liberal guilt but with a disarming blend of detachment and avidity. "It is always thus" the paintings imply. They seem better to me each time I see them. Golub made considerable amounts of not very good art, too, usually based on Greek and Roman myths and motifs that, though they were alive to him, are generic to most of us. But even his failed work conveys a bursting, gleefully contrarian sprit. And the quick, colorful pictures at the Drawing Center, from the last five years of the artist's life, make for the freshest, youngest feeling show in town.

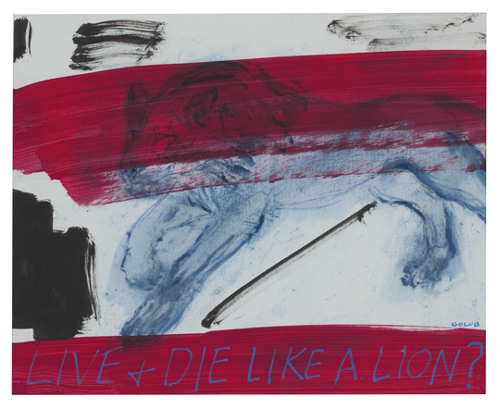

The forty-three drawings are nearly all eight by ten inches, on vellum, Bristol board, or paper, and are handsomely installed. Brett Littman, the Drawing Center's executive director, who curated the show, has had them floated in identical white frames and hung on walls painted a variant of one of Golub's favorite symbolic colors: Pompeian-oxide red, cruelly powerful. (Another was a soft light blue, poignantly redolent of innocent summer skies.) Sketched images on grounds of dragged and smeared oils in brilliant hues exfoliate themes of eroticism and violent emotion. Most bear scrawled internal captions. The earliest from 1999, epitomizes the over-all mood by embellishing a gaping skull with the words "Fuck death." Golub didn't go into the night gently; he took exasperated note of its encroachment. He marshaled a long-running totemic bestiary of lions (majestic force) and dogs (savagery) along with the occasional sphinx, centaur and satyr. Littman used on inscription to title the show: Live & Die Like a Lion?" I love that question mark, which is echt Golub in its glancing humility. Vitrines display files of photographs, most torn from magazines, which inspired the drawnings. Pornography predominates, employed with a life-celebrating joviality that feels positively wholesome. Only four drawings, done almost entirely in black, seem directly political: a bound corpse ("Whereabouts unknown"); a slumping man tied to a post ("No escape now"); a smiling, shirtless dude, with a "don't tread on me" tattoo, danndling a rifle ("Payback Time"); and an anguished figure embedded in a fencelike grid ("In the barbed wire cosmos"). One large canvas, which Golub began in 2001 but didn't have the strength to finish, presents energetic sketches of two loping lionesses, in white chalk and brown crayon. It is beautiful.

I knew Golub as an engaging man, bald and impish, who relished his outsider status as a member of a bohemian community of two: himself and his wife, Nancy Spero, a rail-thin woman of eager charm. They met at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago in the late nineteen-forties, after Golub's wartime service in the Army, and married in 1951. They brought up three sons. Spero, who died in 2009, made large, austere drawings and collages, laced with literary allusions, on themes of female suffering and pride. Toward the end of their lives, she was more publicly successful than he was, especially in the Europe. This made Golub cranky, but his grouches were easily accommodated in the couple's bantering style, which made a comedy of their differences. (He worded by day, she was in the wee hours; he was boisterous and vulnerable, she diffident and resilient.) Their union preserved certain passionate convictions of their youth, chiefly a loyalty to humanist strains in modern art-the rhetorical figuration of Munch, Ensor, Rouault, Giacometti, Dubuffet, and the Picasso of "Guernica"-against the grain of American high taste after Abstract Expressionism. A postwar fashion for humanist styles expired in a famous flop of an exhibition, "New Images of Man," at the Museum of Modern Art, in 1959, which perhaps only Golub, of the younger artists included, survived without despair. He and Spero were amply sophisticated. (He was a more pertinacious reader of art criticism than any other artist I have met, with lively arguments always on tap for recent twists in the discourse.) But they reminded each other to stay combative and visceral, Chicago toughies abjuring decorative and ironic finesses that could have opened doors to them in New York.

Golub's parents were Jewish immigrants from Ukraine and Lithuania; his father was a doctor. Golub made art from early on but planned to become an art historian, studying at the University of Chicago. He told his biographer, Gerald Marzorati ("A Painter of Darkness," 1990), of the formative, lasting shock to him of "Guernica," when it was shown at the Chicago Arts Club, in 1939. He also described the furor among students when Jackson Pollock's paintings first came to Chicago, in 1948: "We literally ran up to the galleries," but the big canvases "did nothing for me....What i saw were patterns of color." Golub later came around to New York School of aesthetics of materials and scale, expanding on the compact images of beefy, ravaged men that he had painted in the fifties. But his stubborn focus on dramatic figures kept the effects subliminal. In the sixties, he took to working on unstretched canvases, hung like pelts of distressed skin. His "Gigantomachies"- naked men in mortal combat- gave way to sorrowing scenes of the Vietnam War, which he and Spero actively protested. At loose ends thereafter, he lay low for years while making a long series of strange small paintings from photographs of the powerful- Nelson Rockefeller, Francisco Franco, Fidel Castro- as if trying to isolate a secret isotope of power; but all the magnificos emerge looking banally ordinary. Then news of brutal events in Latin America and Africa triggered his major work, after which he returned to less effective, generalized mythic content. The zestfully personal pictures at the Drawing Center constitute a sweet last minute coup.

The epithet "political artists" brands Golub. What does it mean? It suggests over protest, addressing social questions with answers ready to hand: someone or something to blame. That doesn't jibe with the complexity of even Golub's most topical work. He was a citizen of the left, but his mentality strikes me as classically conservative: convinced of innate human wickedness, to a degree almost beyond caring. In this, he evokes the obvious precedent of Goya, whose diabolical humor, though feathered with compassion, scorns any hope of amelioration that relies on people being good. The pertinent politics of Golub's case is cultural. He stands for a view that art should not, and really cannot, be a serene island off the chaotic mainland of human experience. Anything that anyone does, anywhere, implicates everybody. Art can dramatize that. The exercise needn't be lugubrious. The recurrently astonishing gaiety of Golub's imagination in dire neighborhoods of dirt and blood, advertises how free a mind may be that dares itself to welcome truths that are respectable exclusively on being true.

Please click here to view the actual article.

Seraphin Gallery l Contemporary Philadelphia Art Gallery and Art Consultant

1108 Pine St. l 215-923-7000 l seraphin@seraphingallery.com